There are no easy answers to speech, censorship and internet freedoms given the current state of the internet. Some solutions are better than others, but there’s no perfect answer.

If someone suggests there’s a simple answer, they’re probably wrong.

As Harvard internet law professor Jonathan Zittrain explained in June:

The truth is that every plausible configuration of social media in 2020 is unpalatable. Although we don’t have consensus about what we want, no one would ask for what we currently have: a world in which two unelected entrepreneurs are in a position to monitor billions of expressions a day, serve as arbiters of truth, and decide what messages are amplified or demoted.

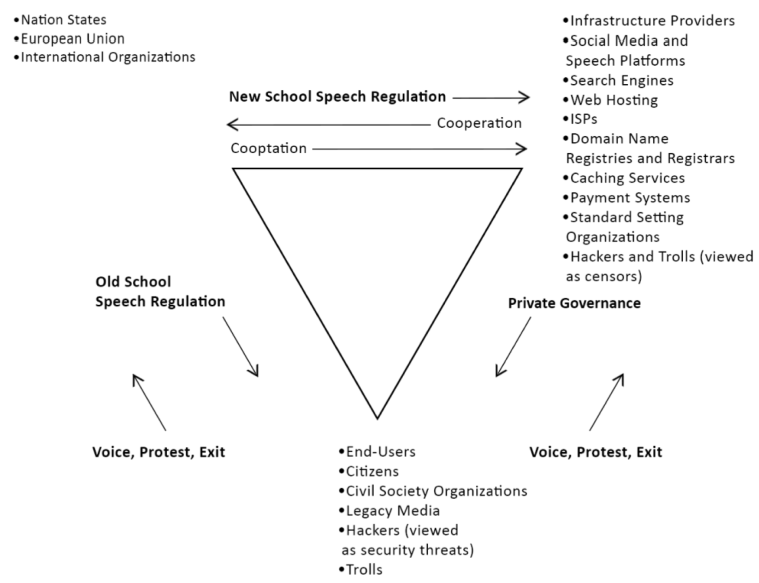

In a technological revolution, old systems break before new systems are in place. Jack Balkin, Mike Godwin and many others have explored how the traditional dualist understanding of free speech as “people vs government” is dead. What we have online is now more of a triangle between (1) government, (2) private intermediaries, (3) users/speakers. Private companies include “edge” platforms like social media sites, but also infrastructure providers (like hosting services, domain registrars, payment processors, etc). Critically, the intermediaries have free speech rights against government, but are also in a position to block speech from users.

This is complicated, and new.

There are no easy answers to these problems. Smart people — programmers, technologists, academics, thought leaders, activists, advocacy groups, entrepreneurs — have been trying to solve these particular internet freedom problems for as long as we’ve had mainstream social media pulling people away from the open web.

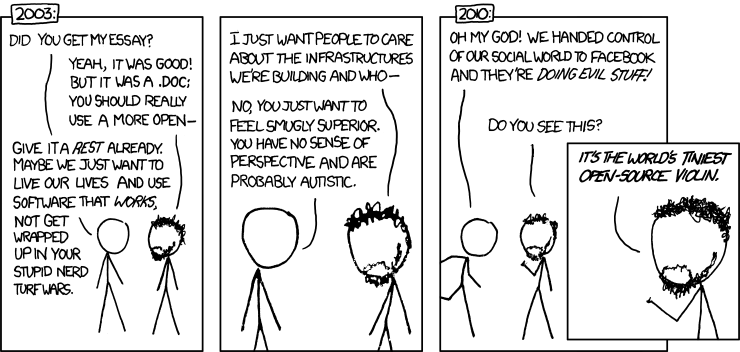

In a way, it’s frustrating to see many people around me suddenly panicked about internet freedoms and privacy, when most people usually respond with disinterest or dismissal to those who try to draw attention to these issues. Part of me wants to pick up my violin.

That said, it’s also encouraging that people are taking an interest in these issues now, but it’s important that we don’t panic and rush to “solutions” that actually just make the problems worse. There is no “Great Purge” or “digital Gulag,” but there are real problems for online public discourse.

While I have your attention for a moment, there are some key issues to understand if we’re going to move forward in a productive way. In this post, I’ll focus on understanding the problems; in my next post, I’ll talk about problematic and promising ways to respond.

The Main Problem: Proprietary Walled Gardens

In one sense, people have more freedom to speak than ever before. Prior to the internet, the average person wouldn’t have a platform to reach a global audience, and social media makes it efficient to find like-minded people. But with new opportunities come new problems as well.

The primary problem is that we now depend too much on a couple private companies for public discourse. This distorts public discourse, and puts enormous power in the hands of a couple private actors. I was struck by how corporate our view of the internet is while watching Ralph Breaks the Internet – the internet is visualized as either big corporate skyscrapers, or sketchy back alleys.

Recently, I saw someone make a quip (ironically, on Twitter) that Facebook and Twitter are perfect examples of socialism because rich people censor speech and control your access to information. It’s really important to remember this is not socialism at all. This is actually a perfect example of capitalism. Markets can restrict freedom too.

However, it’s not just that Facebook and Twitter are private companies, but it’s specifically that mainstream social media platforms are proprietary, centralized, walled gardens. Mainstream social media is proprietary (privately owned), centralized (a few giant websites), and walled off and separated from the open internet.

Perhaps it’s easiest to explain through an example: Email is not like this. If you want to use Gmail, you can still talk to a friend with a Hotmail account, or run your own email server – and, not that there aren’t serious challenges, but no one is the “boss” of email. The same goes for blogs and linking. Or with phones, you can call someone regardless of which phone company they use. However, if you want to use Twitter, you can’t communicate with a friend on Facebook. If you use iMessage, you can’t message someone on Signal. These platforms are walled off and separate from each other and the rest of the internet, and all the data lives in separate silos, owned by a couple private companies.

It’s like we’ve replaced the public square with Disneyland (or Duloc), or with a shopping mall. As users, we’re just guests, and we have no guaranteed freedoms in the places where so much of the public conversation is taking place. This is the environment from which other problems emerge.

It’s Not Just Cancel Culture: Content Moderation at Scale is Impossible

Our daily internet experience is no longer millions of hyperlinked websites, but mostly five websites full of screenshots of the other four. When so much of our conversation happens on a few giant walled garden platforms, the content moderation policies of those platforms have enormous power to shape public discourse – and there’s little transparency or accountability.

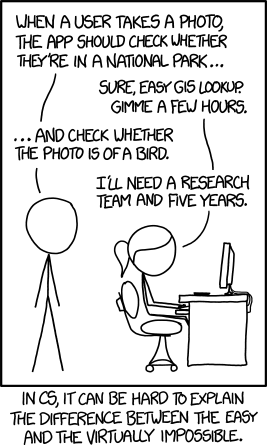

However, the reality is that this isn’t some attempt to censor unpopular views. The reality is that content moderation at scale is hard.

Parler is a great example of naively thinking there are easy answers. In May 2020, Parler published a dramatic Declaration of Internet Independence (perhaps not realizing that’s been done before), and they promised to moderate content “based off the FCC and Supreme court of the United States” (whatever that means). Parler’s CEO said in June that, “if you can say it on the streets of New York, you can say it on Parler.” Just days later, Parler found out that doesn’t work. They banned a ton of users, and Parler’s CEO learned very quickly that they needed rules to stop people from posting pictures of their fecal matter, selecting obscene usernames, spamming others (all of which would be allowed on the streets of New York or by the first amendment), or threatening to kill people (it isn’t always obvious what constitutes a legal threat). Even after January 6, they still think that “algorithms” will be able to police content on their platform.

It’s not just that content moderation at scale is hard, but it’s actually impossible to do well. There’s no perfect policy, there’s no solution that will make everyone happy, and there will always be many, many mistakes and bad decisions – even a very high accuracy rate leaves millions of failures when these platforms are dealing with millions of daily posts. As Mike Masnick explains:

Content moderation at scale is impossible to do well. More specifically, it will always end up frustrating very large segments of the population and will always fail to accurately represent the “proper” level of moderation of anyone…

First, the most obvious one: any moderation is likely to end up pissing off those who are moderated… Now, some might argue the obvious response to this is to do no moderation at all, but that fails for the obvious reason that many people would greatly prefer some level of moderation, especially given that any unmoderated area of the internet quickly fills up with spam, not to mention abusive and harassing content…

Second, moderation is, inherently, a subjective practice. Despite some people’s desire to have content moderation be more scientific and objective, that’s impossible. By definition, content moderation is always going to rely on judgment calls, and many of the judgment calls will end up in gray areas where lots of people’s opinions may differ greatly. Indeed, one of the problems of content moderation that we’ve highlighted over the years is that to make good decisions you often need a tremendous amount of context, and there’s simply no way to adequately provide that at scale in a manner that actually works. That is, when doing content moderation at scale, you need to set rules, but rules leave little to no room for understanding context and applying it appropriately. And thus, you get lots of crazy edge cases that end up looking bad.

Third, people truly underestimate the impact that “scale” has on this equation… On Facebook alone a recent report noted that there are 350 million photos uploaded every single day. And that’s just photos. If there’s a 99.9% accuracy rate, it’s still going to make “mistakes” on 350,000 images. Every. Single. Day. So, add another 350,000 mistakes the next day. And the next. And the next. And so on.

And, even if you could achieve such high “accuracy” and with so many mistakes, it wouldn’t be difficult for, say, a journalist to go searching and find a bunch of those mistakes — and point them out. This will often come attached to a line like “well, if a reporter can find those bad calls, why can’t Facebook?” which leaves out that Facebook DID find that other 99.9%. Obviously, these numbers are just illustrative, but the point stands that when you’re doing content moderation at scale, the scale part means that even if you’re very, very, very, very good, you will still make a ridiculous number of mistakes in absolute numbers every single day.

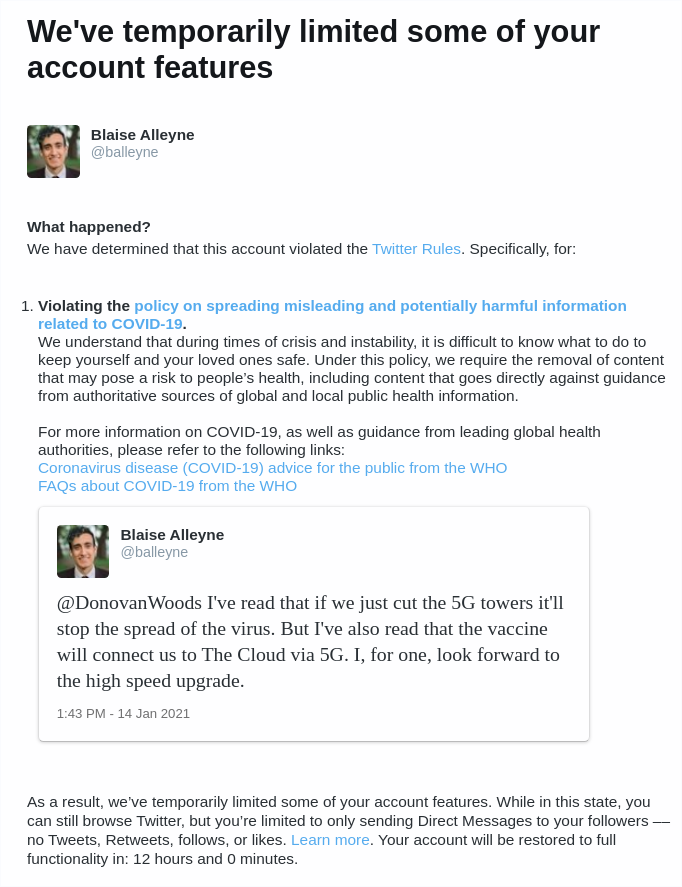

Fun fact: As I write this, I’m currently suspended on Twitter for spreading COVID-19 misinformation… because I was making fun of 5G conspiracy theories.

In 2018, Radiolab produced a fantastic hour-long podcast on content moderation at Facebook: Post No Evil.

They trace Facebook from an initial two page content moderation document in 2008 through 10 years of trying to handle different complex situations. They track internal debate from breastfeeding photos (nipples covered? how old can the child be? what about humans breastfeeding goats?) to language on protected and unprotected classes (“white men” versus “black children” — try to guess who gets protection and why) to victim photography from the Boston marathon bombing (allowed) and Mexican drug cartel violence (banned) – nevermind the trauma faced by low-wage employees as Facebook’s content moderation team expanded from a handful of people in a room to thousands of content moderation employees worldwide.

At one point, a Facebook employee explains: “This is a utilitarian document. It’s not about being right 100 percent of the time. It’s about being able to execute effectively.” Simon Adler expands, “In other words we’re not trying to be perfect here, and we’re not even necessarily trying to be 100 percent just or fair, we’re just trying to make something that works.” (cf. COVID-19 public health measures…)

The episode is a wild ride, and it doesn’t even touch upon tough questions surrounding Trump, politics, and elections (in the US or elsewhere).

This is not to say that cancel culture isn’t a real problem online. (Take the example of a feminist getting banned for disagreeing with the new-as-of-a-few-years-ago orthodoxy on gender, or controversial reporting being buried during an election, just for a couple controversial examples.) But it’s not primarily a problem of targeted, ideological censorship. Conservatives think they’re being targeted for traditional views on sexuality, while the sexual revolutionaries think they’re being targeted for the opposite views. (Perhaps it’s the additional filter bubble problem that leads us to mostly hear about “our side” being censored, and we extrapolate from there.)

In reality, it’s the fact that we’re all relying on a couple private walled garden websites to attempt the impossible job of moderating content with little transparency, accountability, or oversight, on platforms where we’re just tenants – and tenants can be evicted.

The need for real solutions

Cancel culture is a real problem, but there is no social media “neutral.” There is no tenable free speech absolutism online (as Parler quickly learned), and drawing boundaries is hard. As someone who’s been assaulted for exercising my freedom of expression, I’m very concerned about the range of allowable speech being narrowed and the steps people will take to silence those with whom they disagree. But there is no neutral “free speech” position on social media, only difficult conversations about how to draw lines and how to enforce them.

If you think it’s a simple ideological problem (“Big Tech is imposing it’s left wing agenda and cancelling speech it disagrees with” OR “Big Tech is too tolerant of radicalizing speech online and needs to crack down”), you wind up with “solutions” that don’t actually fix the real problems (e.g. Parler).

You wind up with technopanics and people leaving WhatsApp (which is still end-to-end encrypted so Facebook/WhatsApp can’t see your messages) for Telegram (where the company can view most of your messages on its server…). You get misinformed “gotcha” questions (“If Big Tech can ban Parler, why can’t they ban child porn?” as if “child porn” is a single website and not a complex problem) or “gotcha” situations (“aha! My post was banned, but it took them days to ban this awful stuff I found! Proof of bias!”). You wind up with ignorant legislative solutions that will make the problem worse.

You wind up with people looking for a more benevolent or ideologically-aligned landlords, instead of advocating for tenants’ rights. You wind up with just another brief technopanic, until everyone reverts to their usual habits and forgets about internet freedom and privacy until the next mass panic.

You don’t get real change.

In Part 2, I’ll explore the range of problematic responses, and explain other efforts that are far more promising.