Refuting conspiracy theory arguments is exhausting. It’s like battling an army of orcs or white walkers. It’s not very hard to take down any given individual, but they just keep coming.

It’s a pattern of overwhelming, and these arguments are almost always smokescreens for the true beliefs — and the true basis of those beliefs. It’s a proxy war in an epistemic crisis. It doesn’t matter how effectively you refute any argument, because any particular argument doesn’t really matter to the person invested in a conspiracy theory — they have another one ready to take its place. Because it’s not about the argument at the end of the day. It’s about how we even determine truth.

This matters because conspiracy thinking has real world consequences.

I’m tired of fighting white walkers; we need to go after the Night King. I’m tired of fighting orcs; we must destroy the ring.

My winter reading is focused on reverse engineering what I’ve been seeing, especially over the past year. It’s a journey to the land of always winter.

Intellectual Anti-Patterns

This is also about learning to think better. The first chapter of the first book I’m reading points out that everyone believes some conspiracy theories, and also that some conspiracy theories are true. The problem doesn’t lie in positing a conspiracy per se; the problem lies in the patterns that surround conspiracy theory thinking: unfalsifiable claims, poor standards for judging evidence which leads to unjustified assent, uncritical suspicion that leads to gullibility, mistrust that leads to alienation and a separation from the rest of society, etc.

These are logical fallacies, intellectual anti-patterns, a way of thinking that may feel like critical thinking, yet it’s really not thinking critically enough.

In software design, an anti-pattern is a commonly-used process or structure that, despite initially appearing to be an appropriate and effective response to a problem, has more bad consequences than good ones. It’s the rejection of an existing solution to a problem that is already documented, repeatable, and proven to be effective for another solution which is not.

Conspiracy thinking relies on intellectual anti-patterns to determine the truth.

Everyone can fall into this type of thinking. The way to build immunity is to understand and learn to recognize the anti-patterns.

I’m fortunate to have many intelligent friends — with whom I agree and with whom I disagree — who have challenged me to think more deeply on these subjects, and exposed to me to other thinkers as well. I will steal mercilessly from my allies and interlocutors as I begin to write about the discussions I’ve been having and what I’ve been learning.

Three Guides

Through many conversations over the past year, and especially the past few months, I’ve selected three guides on this journey down the next circle of the inferno: Joseph Uscinski, Yochai Benkler and Eric Oliver.

I’ll write more as I read and discuss more, but in the meantime, I just wanted to introduce my winter reading list for anyone else looking for some dragonglass or a map of Mordor.

Joseph Uscinski on Conspiracy Theories

After evaluating a dozen books on understanding conspiracy theories, I’ve decided to start with Joseph Uscinski’s Conspiracy Theories: A Primer.

His 2017 talk with a provocative title (yet actually neutral and objective take if you hear him out) was excellent: Conspiracy Theories are for Losers. And his website has links to more recent articles on COVID-19, QAnon, and other topics.

From this book, I hope to get a decent orientation on conspiracy theories and conspiracy thinking.

Yochai Benkler on Network Misinformation

I’m far behind in my podcast queue, and thus recently listened to this June 2019 interview with Yochai Benkler on the Techdirt podcast about his book, Network Propoganda (co-authored with Robert Faris and Hal Roberts). While it seems like he may have a blindspot for cultural and religious issues, the central findings of their research are fascinating and relevant.

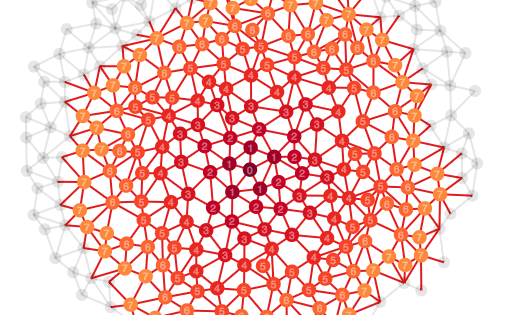

These Harvard internet guys from the Berkman Klein Center went looking to study polarization in US information ecosystems by tracking how information is shared through traditional and social media. They expected to find symmetric polarization: right and left. Instead, they found asymmetric polarization: right and rest. They found a right wing information ecosystem that was an insular outrage feedback loop, cut off from the rest of the information ecosystem — even from the centre right. This caught my attention because it has great explanatory power for what I’ve been noticing in my own circles.

Eric Oliver on Intuitionism

Finally, this podcast conversation with Eric Oliver on conspiracy thinking was fascinating.

The central thesis is that “deeper than red or blue, liberal or conservative, we’re actually divided by intuitionists and rationalists.” I get the impression that this political science professor has an Enlightenment caricature understanding of religious belief, however the psychological distinction between intuitionism and rationalism immediately jumped out to me as profound. This theory also has great explanatory power for what I’ve been seeing.

They can predict how likely someone is to believe conspiracy theories based on where they fit on a spectrum from rationalism to intuitionism. Check out this exchange:

Paul Rand: So, if we have listeners that are listening to this episode of Big brains, and they’re sitting there thinking, well interesting, I wonder if I’m an intuitionist or a rationalist. How do you…do you look at somebody and say, oh I can tell who you are. Is there a mode of thinking that helps assess that?

Eric Oliver: So I can offer a few quick questions that are pretty good diagnostic. So, we typically ask people in our surveys a couple of things and say, just tell us the first answer that comes to your mind and say: would you rather stab a photograph of your family five times with a sharp knife or stick your hand in a bowl of cockroaches?

Paul Rand:Â That’s a really crazy question.

Eric Oliver: It gets better.Â

Paul Rand: Thank you by the way for not asking for an answer from me.

Eric Oliver:Â And I’ll explain the logic behind that. Would you rather sleep in laundered pajamas once worn by Charles Manson or pick a nickel off the ground and put it in your mouth? Would you rather spend the night in that dingy bus station or spend the night in a luxurious house where a family was once murdered?

Eric Oliver: What we’re doing with these questions is we are asking people to compare basically what our tangible costs to symbolic cost. So, for example, stabbing a photograph of our family, it’s just a piece of paper. But, for a lot of people, stabbing a photograph feels like we’re violating and are doing harm to a family member. It’s like the equivalent of a voodoo doll. And so that’s very emotionally costly for them seem. Similarly, sleeping in launder pajamas once worn by Charles Manson, they’re just cloth on our body, but the idea that Charles Manson had contact with them, it’s a contagion heuristic. So these things end up being emotionally costly. And so people who are very sensitive to these types of heuristics are people who tend to then rely on their intuitions a lot more.

So, if I have time for a third book, it’ll be Enchanted America by Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood.

I hope these three guides will help me to better triangulate the truth. I’ll keep you posted.

3 thoughts on “Reverse engineering the intellectual anti-patterns of conspiracy thinking”

Thanks Blaise.

Looking forward to hearing more about your findings!

Bravo on this post! Your expertise and writing proficiency make for a compelling read. Excited to follow your future articles. Thank you for sharing your insights!