When I get frustrated about people’s response to public health measures, I rant on social media. When I rant on social media, some of the conversations are painful, but… others are just fantastic. Perhaps I thrive on genuine dialogue, which forces you to try to understand another person, and to put into words what you’re thinking — and that inspires me to write and share.

This was my latest rant (inspired by a response to US election-rigging conspiracy theories):

The numbers aren’t rising, we’re just doing more tests

Okay, the numbers are rising, but it’s the test positivity rate that matters

Okay, test positivity rate is high and cases are rising, but hospitalizations aren’t risingYou are here => Okay, hospitalizations are rising, but the hospitals aren’t overwhelmed

– Okay, the hospitals are overwhelmed, but people aren’t dying – the death rate is barely increasing

– Okay, people are dying, but… Sweden? Herd immunity? I’m “too healthy to wear a mask”?

As we work our way down a predictable checklist of shifting objections to public health measures, I’m honestly not sure what the final version of the objection will be…

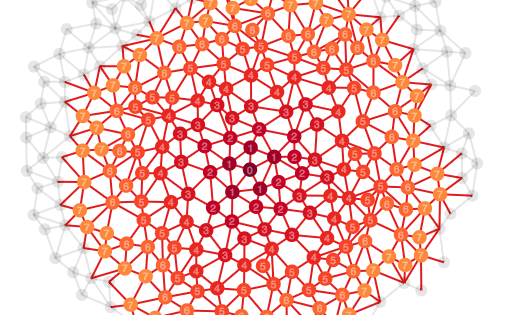

It’s frustrating that people don’t understand exponential math (even when they think they do), and that amidst all the uncertainty of trying to predict the future in this pandemic, only one thing seems certain: this is going to get worse before it gets better.

If you don’t think there’s any danger or risk, then I need to write another blog post for you. However, I think I can put into words two things that have been the most frustrating during the pandemic about resistance to public health measures.

It’s not about you

Some people have asked me, why are you afraid? I found this a strange question at first. Fear is not an emotion I have felt at all during the pandemic. I’m not afraid of getting into a car accident either — however I try to be very cautious in a car, because I understand that statistically speaking some of the most dangerous parts of my week are when I’m in a car. It’s rational and responsible to respond to actual risk with the appropriate amount of caution — for me and for those around me. I still drive, and I still do things during the pandemic, but I’m conscious and, to what I think is an appropriate degree, I’m careful.

Some people are confused about being careful too. Many people who are critical of public health measures seem to think I’m concerned about myself — like when I wear a mask, it’s because I’m concerned about getting the virus. It’s tricky to wear a mask in a way that offers you much of any protection — and I only bother to do that in a high risk scenario (e.g. after waiting in line for a COVID-19 test alongside other symptomatic people). However, it’s simple to wear a mask in a way that offers some protection to others — just cover your mouth and nose.

Like, exponential math, people say they understand asymptomatic spread, but then say things that make it clear that they don’t. Asymptomatic spread means you don’t know if you have the virus. “I’m too healthy to wear a mask” is a stupid thing to say. The nature of asymptomatic spread means that you don’t know if you’re healthy. Unless you’ve just self-isolated for two weeks or something, you don’t actually know if you have the virus. Thus, the responsible thing to do is to assume that you may have it, and be careful out of concern for others.

“If you’re afraid of getting the virus, you can stay home.” Sure, but I’m not afraid of getting the virus — I’m concerned about spreading the virus to other people. “Well, if you’re concerned about spreading the virus to other people, you can stay home.”

This is what gets me most, the hyper-individualism. I’m not being careful because I’m afraid or because I want to keep my own hands clean — and not be personally responsible for spreading the virus to others. I’m being careful because I care about others. My concern isn’t that my own hands are clean. My concern is that other people are in danger. The fact that my own hands are clean is irrelevant if other people are still in danger.

As usual, the pro-choice argument doesn’t work. The public health concern isn’t simply about personal choice — yeah, I can make my own choices to stay safe and avoid being responsible for spreading the virus to others. The public health concern is that people are in danger.

It’s not about you.

Public health measures enable us to do more

In my latest discussion about the importance of public health measures, I couldn’t help but think of the show My Last Days and the story of Anthony Carbajal living with ALS, which moved me to tears when my aunt shared it on Facebook last year. In particular, the scene with his neurologist, Dr. Jeffery Rosenfeld, which starts at 9:53.

Anthony shares that he’s been trying to get over the idea of a tracheotomy, after seeing his mom go through the procedure a year prior. He says, “I see my mom living a really fulfilling life, but I’m also scared of that decision.”

It’s Dr. Rosenfeld’s response to Anthony that stands out to me:

These are not markers of disease progression. These are ways to facilitate where you’re at, and raise your level of function.

And it hit me — this is what so many people don’t understand about the public health measures.

One way to view public health measures is as a restriction on individual liberties (and, they are). However, from a medical perspective, these interventions are not only about preventing the spread of the virus, but also about raising our level of function during a pandemic. The public health measures protect us by restricting freedom, but they also enable us to do more.

The nature of the virus is so incredibly tragic. There’s something profoundly inhumane about this scenario where we all must act as if we’re infected, act as though we’re a danger to others, stay distanced and stay isolated. It’s awful. It’s so hard. But that’s not some medical officer’s fault. That’s the nature of the virus.

I recently listened to this profound story on the power of touch during the AIDS epidemic, when touch was irrationally suspect. The nature of this virus, of this pandemic, has made touch rationally a risk.

A friend of mine lost a grandparent in the Spring, when only 10 people were allowed at a funeral. Another friend of mine lost a grandparent overseas, and wasn’t able to attend the funeral because of the self-isolation periods that would be required with international travel. I lost my grandfather this Summer. And that is always difficult, but it is even more difficult during a pandemic, when physical distancing is necessary, and when we were unable to hold a funeral reception.

Yet, we were fortunate to be able to hold a visitation and many people were able to come. Though we could only fill 30% of the parish church my grandfather helped to build, many people were able to attend the requiem mass and burial. Public health measures — like mask mandates, registration for contact tracing, and physical distancing aids — enabled this to happen during a pandemic.

We are so focused on what public health measures prevent us from doing — and they prevent us from doing so many beautiful and wonderful and essential things. That’s the nature of the virus, the reality of the pandemic. What about the things that public health measures enable us to do in the meantime?

There’s a long road ahead still. I would rather face it with public health measures that not only protect us from the danger of the pandemic, but that also enable us to do more now — as we await the end of the crisis.

One thought on “Clean hands can do more”

Thank you Blaise. You are always so thoughtful and articulate.